How to design an environmental policy on air pollution

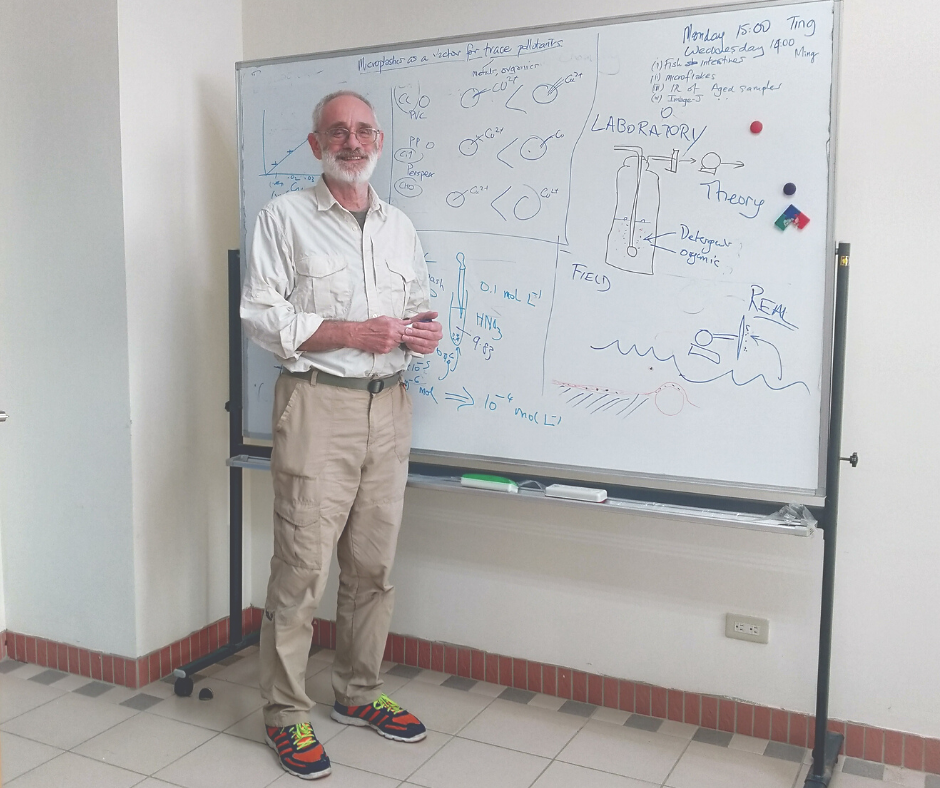

Even the best intentions without thorough research can cause a disaster. In the 1930s, Thomas Midgley synthetized chlorofluorocarbons to replace poisonous ammonia in refrigerators; the serious depletion of the ozone layer caused by his invention was discovered only 30 years after his death. “If you don't understand the underlying science, you are at risk of making the wrong decision”, warned Distinguished Research Chair Professor Peter Brimblecombe of the Department of Marine Environment and Engineering at National Sun Yat-sen University.

To find an effective solution to our environmental problems, “we have to get agencies deeply interconnected and working together in parallel”, says Professor Brimblecombe. Such problems as air pollution require the cooperation of several government entities, not only those dealing with environmental protection but also transportation and housing, to avoid reaching a piecemeal solution. What is more, before the legislative process of a pollution-related policy can kick off, thorough research needs to be done beforehand to avoid any possible mistakes.

Some of such mistakes can be based on different social myths. We have always believed that trees are lungs of the city, but surprisingly, trees don't make a major contribution to the city's air quality, according to Professor Brimblecombe’s recent research. Trees in the city “don't absorb pollutants but block them” and may even lead to locally increased pollutant concentrations. “Trees can absorb carbon dioxide on a planetary scale over periods of months but the air in cities is only there for an hour, 30 minutes, 10 minutes”.

Drawing an environmental policy is not as easy as it might seem – “we need to think beyond simple actions”, said Professor Brimblecombe. It is vital to consider every possible outcome arising from a decision. “Regulators have traditionally taken the view that regulation involves stopping emissions. They say, if we eliminate half the cars on the road, we cut the emissions in half. But that's not sensible, because there will be some other ways in which people will find to move about”, said Professor Brimblecombe. Although a reduction of the amount of emissions is a positive change, it will not necessarily contribute to reducing the health risks caused by air pollutants. To reduce health outcomes, regulators need to first identify the sources of the particular pollution people are exposed to.

Radical containment of polluting industries might be a risky solution, as this may give rise to illegal production or smaller, poorly-regulated production sites. Recently, to reduce accidents and air pollution, “China has really been able to cut back on the use of fireworks dramatically“, said Professor Brimblecombe. The domestic utilization of fireworks in China is declining, and so are the exports. However, these positive changes do not come without side effects. “Large fireworks factories have closed because there's so little demand for fireworks but smaller ones have begun to open and these have much poorer environmental and safety regulations, so the number of explosions now in Chinese factories has increased”.

A great way to reduce overall emissions is to reduce the number of combustion sources, either by promoting public transportation or transferring the combustion source to a power plant, as “it's easier to regulate a large industry, which also has the technical skill”. Electric vehicles seem to be a positive trend. Yet, personal electric cars and scooters utilize resources and they still emit pollutants – metal and rubber particles, explained Professor Brimblecombe. “The danger of going the electric route is that we ultimately avoid the notion of public transport as a kind of service”, he emphasizes.

Different types of urban areas have their specific problems. Marine air pollution, which source is toxic fuels burned by vessels, lowers the air quality in port cities. “Marine diesel fuels contain quite a lot more toxins than normal diesel, with very high concentrations of vanadium, nickel, and sulfur”. What makes it difficult to control the emissions is that they mostly take place outside any national jurisdiction, said Professor Brimblecombe. What aggravates the problem, even more, is that “most ships are registered in small countries such as the Marshall Islands, Liberia and a few other countries with almost no regulations, so the ships can burn whatever they like”. Shore-side electricity can help reduce the use of toxic fuels; it consists in the provision of electrical power to ships at berth.

Distinguished Research Chair Professor Peter Brimblecombe specializes in atmospheric chemistry. He teaches a course in Marine Air Pollution at the Department of Marine Environment and Engineering and will teach an undergraduate course in Atmospheric Chemistry and Air Pollution starting from September 2020. In February 2020, he published his research result on the influence of parks on a city’s air quality – “Urban park layout and exposure to traffic-derived air pollutants”. Besides air pollution and the related social movements and policy-making, his most recent research interests lie in microplastics and the relation between art and air pollution.

To find an effective solution to our environmental problems, “we have to get agencies deeply interconnected and working together in parallel”, says Professor Brimblecombe. Such problems as air pollution require the cooperation of several government entities, not only those dealing with environmental protection but also transportation and housing, to avoid reaching a piecemeal solution. What is more, before the legislative process of a pollution-related policy can kick off, thorough research needs to be done beforehand to avoid any possible mistakes.

Some of such mistakes can be based on different social myths. We have always believed that trees are lungs of the city, but surprisingly, trees don't make a major contribution to the city's air quality, according to Professor Brimblecombe’s recent research. Trees in the city “don't absorb pollutants but block them” and may even lead to locally increased pollutant concentrations. “Trees can absorb carbon dioxide on a planetary scale over periods of months but the air in cities is only there for an hour, 30 minutes, 10 minutes”.

Drawing an environmental policy is not as easy as it might seem – “we need to think beyond simple actions”, said Professor Brimblecombe. It is vital to consider every possible outcome arising from a decision. “Regulators have traditionally taken the view that regulation involves stopping emissions. They say, if we eliminate half the cars on the road, we cut the emissions in half. But that's not sensible, because there will be some other ways in which people will find to move about”, said Professor Brimblecombe. Although a reduction of the amount of emissions is a positive change, it will not necessarily contribute to reducing the health risks caused by air pollutants. To reduce health outcomes, regulators need to first identify the sources of the particular pollution people are exposed to.

Radical containment of polluting industries might be a risky solution, as this may give rise to illegal production or smaller, poorly-regulated production sites. Recently, to reduce accidents and air pollution, “China has really been able to cut back on the use of fireworks dramatically“, said Professor Brimblecombe. The domestic utilization of fireworks in China is declining, and so are the exports. However, these positive changes do not come without side effects. “Large fireworks factories have closed because there's so little demand for fireworks but smaller ones have begun to open and these have much poorer environmental and safety regulations, so the number of explosions now in Chinese factories has increased”.

A great way to reduce overall emissions is to reduce the number of combustion sources, either by promoting public transportation or transferring the combustion source to a power plant, as “it's easier to regulate a large industry, which also has the technical skill”. Electric vehicles seem to be a positive trend. Yet, personal electric cars and scooters utilize resources and they still emit pollutants – metal and rubber particles, explained Professor Brimblecombe. “The danger of going the electric route is that we ultimately avoid the notion of public transport as a kind of service”, he emphasizes.

Different types of urban areas have their specific problems. Marine air pollution, which source is toxic fuels burned by vessels, lowers the air quality in port cities. “Marine diesel fuels contain quite a lot more toxins than normal diesel, with very high concentrations of vanadium, nickel, and sulfur”. What makes it difficult to control the emissions is that they mostly take place outside any national jurisdiction, said Professor Brimblecombe. What aggravates the problem, even more, is that “most ships are registered in small countries such as the Marshall Islands, Liberia and a few other countries with almost no regulations, so the ships can burn whatever they like”. Shore-side electricity can help reduce the use of toxic fuels; it consists in the provision of electrical power to ships at berth.

Distinguished Research Chair Professor Peter Brimblecombe specializes in atmospheric chemistry. He teaches a course in Marine Air Pollution at the Department of Marine Environment and Engineering and will teach an undergraduate course in Atmospheric Chemistry and Air Pollution starting from September 2020. In February 2020, he published his research result on the influence of parks on a city’s air quality – “Urban park layout and exposure to traffic-derived air pollutants”. Besides air pollution and the related social movements and policy-making, his most recent research interests lie in microplastics and the relation between art and air pollution.

Click Num:

Share