Assistant Professor McConaghy explores universal meaning of Chinese native-soil literature in latest research paper

2022-02-16

“On an intellectual level, you can have a kind of critique of a culture and keep a distance but on an affective level, it is incredibly difficult to completely rend yourself of the culture you grew up in.” Assistant Professor Mark McConaghy of the Department of Chinese Literature at National Sun Yat-sen University has recently published an article in the interdisciplinary Journal of Material Culture entitled “Neither remnants nor commodities: Spirit objects in early twentieth century Chinese regional fiction” in which he analyzes the universal meaning behind selected pieces of Chinese regional fiction.

In the late 1910s, China saw the rise of the May Fourth Movement, a major anti-imperialist, anti-traditionalist, and iconoclastic cultural and political movement, linked to the ideas of cultural enlightenment, science, democracy, foreign philosophies, and ideologies, explained Professor McConaghy. The movement advocated the adoption of “a more direct form of writing and expressing the inner and outer world,” vernacular Mandarin instead of classical Chinese. The latter was “a deeply academic language linked to the ritual study of the Confucian Four Books and Five Classics, disconnected from the lived experience of common people, who spoke a variety of regional dialects.” This is how Chinese regional fiction, also called native-soil or nativist literature, was born.

The native-soil literature presented the conflict that China faced in the early 20th century between the deeply animistic and traditional popular life world and a modern, secular, atomized lifestyle. “It’s about secular intellectuals, committed to modern science, democracy, liberalism, republican values, who write about encounters back in their hometowns, often small rural towns, a very different world from Beijing or Shanghai, very animistic and traditional. Although they are so critical of tradition, the family system, and education based on Confucian learning they received there, they wrote about their hometowns with such love and reverence. I was interested, why do they write about their traditional hometowns in this era of modern revolution in terms of language, writing, politics, art?” To find the answer to this question, Professor McConaghy followed the clue of spirit objects in selected pieces of Chinese native-soil literature. The main character of Yu Dafu’s “In Cold Wind”, a writer-intellectual living in Shanghai, returns home and finds his family’s old ancestral altar dumped in trash. This “invoked a melancholic nostalgia for the hometown life, a world he can no longer politically and socially participate in”, and makes him bring the altar back to Shanghai, eventually becoming so overwhelmed with melancholic affect that he too gets down on his knees and prays. “On an intellectual level, you can have a kind of critique of a culture and keep a distance but on an affective level, you can’t reject the culture you grew up in.”

Though critical of traditional popular culture, native-soil literature conveys empathy. One of Professor McConaghy’s favorite stories is Lu Xun’s “New Year’s Sacrifice”, which dramatizes the inability of the narrator, a May Fourth intellectual, to respond to the spiritual concerns of his family’s former servant. The narrator is taken aback by her questions, uncertain how to respond to what in his view is superstitious nonsense, and he runs away from her. “His problem is not of deciding his own opinion regarding the existence of souls but to determine what relationship the devout woman has to these concepts and how any answer he might provide her will effect her actions.”

Regional fiction was part of a major debate on what would modern culture be and how would secular values be embedded within China’s animistic culture – a major issue in 20th-century China. After the iconoclastic fervor of the Cultural Revolution, religious practices resurged in the 1980s and native-soil literature became important again as Chinese authors once again searched for the roots of Chinese identity.

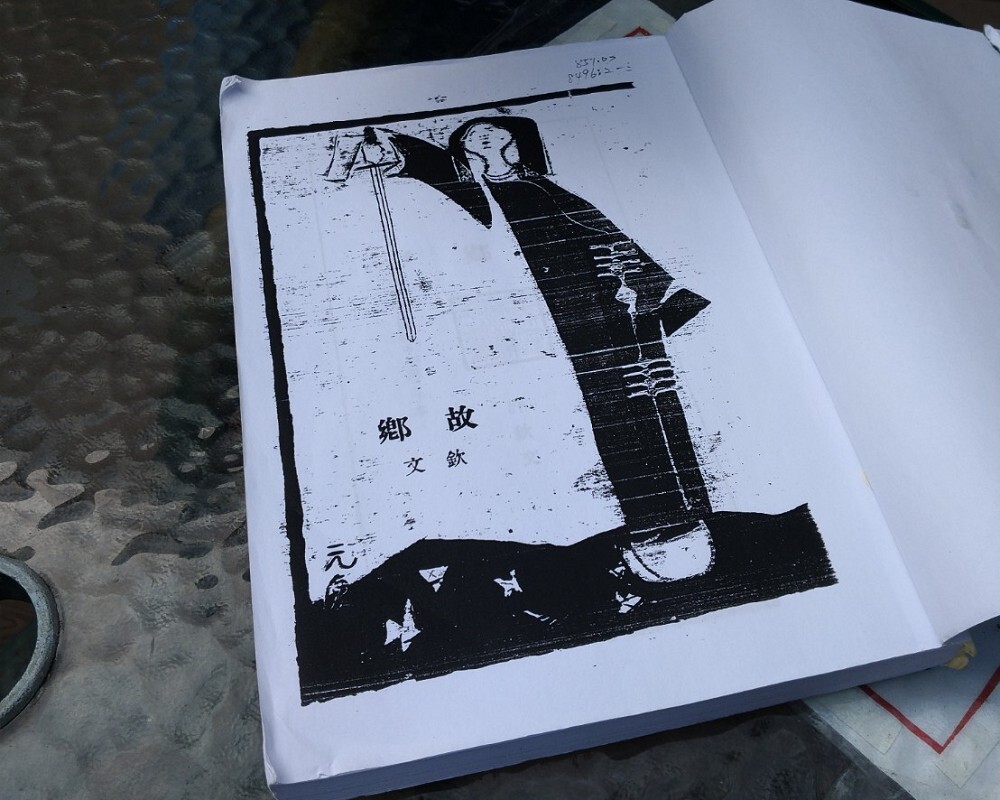

Professor McConaghy’s research interest in this literary movement goes beyond what he included in the latest paper. He explained that with intellectuals exchanging abroad and the circulation of China’s literary journals, the May Fourth Movement found its way to Taiwan, under the Japanese occupation at that time, and led to the surge of Taiwanese nativist literature, “which followed a much different path than the native-soil literature in China.” It recorded the oppression of the colonial period and spurred literary debates “below which surface was a political question – the Taiwanese identity”. Professor McConaghy mentioned Loa Ho’s “Steelyard” as one of the most representative works of Taiwanese nativist literature. “It’s a famous story about the coercive nature of the Japanese colonial state. A peasant is falsely accused of using a fraudulent weight in a vegetable market by a policeman who needs “professional results” (i.e. arrests and fines) before the lunar new year comes. He ends up killing his oppressor – this desperate act represents Taiwanese people’s desire for justice and self-determination and a reasonable state that can provide genuine rule of law and protection. Ho gives voice to people’s frustrations and sense of abandonment as they faced an arbitrary and coercive state.”

“And now we have a Taiwan rooted in the rule of law and justice, realizing its desire for self-determination.”

A powerful nativist movement in Taiwan, linked to the democracy movement, resurged in the 1980s and 90s, focusing on researching Taiwanese history, linguistics, and Taiwanese language writing systems. “It is shaping Taiwanese literature right now, as well as the curriculum of many literature departments across the island, which are becoming more and more Taiwan-centered. Departments of Taiwanese history, literature, culture, have developed across the island over the last two decades.” Professor McConaghy is part of the movement, having taught a course in English at the College of Liberal Arts for local and international students entitled Taiwanese Literature and the Modern World, as well as a graduate seminar on Taiwanese Literary History in the Department of Chinese Literature.

Neither remnants nor commodities: Spirit objects in early twentieth century Chinese regional fiction

https://doi.org/10.1177/13591835211064426

“On an intellectual level, you can have a kind of critique of a culture and keep a distance but on an affective level, it is incredibly difficult to completely rend yourself of the culture you grew up in.” Assistant Professor Mark McConaghy of the Department of Chinese Literature at National Sun Yat-sen University has recently published an article in the interdisciplinary Journal of Material Culture entitled “Neither remnants nor commodities: Spirit objects in early twentieth century Chinese regional fiction” in which he analyzes the universal meaning behind selected pieces of Chinese regional fiction.

In the late 1910s, China saw the rise of the May Fourth Movement, a major anti-imperialist, anti-traditionalist, and iconoclastic cultural and political movement, linked to the ideas of cultural enlightenment, science, democracy, foreign philosophies, and ideologies, explained Professor McConaghy. The movement advocated the adoption of “a more direct form of writing and expressing the inner and outer world,” vernacular Mandarin instead of classical Chinese. The latter was “a deeply academic language linked to the ritual study of the Confucian Four Books and Five Classics, disconnected from the lived experience of common people, who spoke a variety of regional dialects.” This is how Chinese regional fiction, also called native-soil or nativist literature, was born.

The native-soil literature presented the conflict that China faced in the early 20th century between the deeply animistic and traditional popular life world and a modern, secular, atomized lifestyle. “It’s about secular intellectuals, committed to modern science, democracy, liberalism, republican values, who write about encounters back in their hometowns, often small rural towns, a very different world from Beijing or Shanghai, very animistic and traditional. Although they are so critical of tradition, the family system, and education based on Confucian learning they received there, they wrote about their hometowns with such love and reverence. I was interested, why do they write about their traditional hometowns in this era of modern revolution in terms of language, writing, politics, art?” To find the answer to this question, Professor McConaghy followed the clue of spirit objects in selected pieces of Chinese native-soil literature. The main character of Yu Dafu’s “In Cold Wind”, a writer-intellectual living in Shanghai, returns home and finds his family’s old ancestral altar dumped in trash. This “invoked a melancholic nostalgia for the hometown life, a world he can no longer politically and socially participate in”, and makes him bring the altar back to Shanghai, eventually becoming so overwhelmed with melancholic affect that he too gets down on his knees and prays. “On an intellectual level, you can have a kind of critique of a culture and keep a distance but on an affective level, you can’t reject the culture you grew up in.”

Though critical of traditional popular culture, native-soil literature conveys empathy. One of Professor McConaghy’s favorite stories is Lu Xun’s “New Year’s Sacrifice”, which dramatizes the inability of the narrator, a May Fourth intellectual, to respond to the spiritual concerns of his family’s former servant. The narrator is taken aback by her questions, uncertain how to respond to what in his view is superstitious nonsense, and he runs away from her. “His problem is not of deciding his own opinion regarding the existence of souls but to determine what relationship the devout woman has to these concepts and how any answer he might provide her will effect her actions.”

Regional fiction was part of a major debate on what would modern culture be and how would secular values be embedded within China’s animistic culture – a major issue in 20th-century China. After the iconoclastic fervor of the Cultural Revolution, religious practices resurged in the 1980s and native-soil literature became important again as Chinese authors once again searched for the roots of Chinese identity.

Professor McConaghy’s research interest in this literary movement goes beyond what he included in the latest paper. He explained that with intellectuals exchanging abroad and the circulation of China’s literary journals, the May Fourth Movement found its way to Taiwan, under the Japanese occupation at that time, and led to the surge of Taiwanese nativist literature, “which followed a much different path than the native-soil literature in China.” It recorded the oppression of the colonial period and spurred literary debates “below which surface was a political question – the Taiwanese identity”. Professor McConaghy mentioned Loa Ho’s “Steelyard” as one of the most representative works of Taiwanese nativist literature. “It’s a famous story about the coercive nature of the Japanese colonial state. A peasant is falsely accused of using a fraudulent weight in a vegetable market by a policeman who needs “professional results” (i.e. arrests and fines) before the lunar new year comes. He ends up killing his oppressor – this desperate act represents Taiwanese people’s desire for justice and self-determination and a reasonable state that can provide genuine rule of law and protection. Ho gives voice to people’s frustrations and sense of abandonment as they faced an arbitrary and coercive state.”

“And now we have a Taiwan rooted in the rule of law and justice, realizing its desire for self-determination.”

A powerful nativist movement in Taiwan, linked to the democracy movement, resurged in the 1980s and 90s, focusing on researching Taiwanese history, linguistics, and Taiwanese language writing systems. “It is shaping Taiwanese literature right now, as well as the curriculum of many literature departments across the island, which are becoming more and more Taiwan-centered. Departments of Taiwanese history, literature, culture, have developed across the island over the last two decades.” Professor McConaghy is part of the movement, having taught a course in English at the College of Liberal Arts for local and international students entitled Taiwanese Literature and the Modern World, as well as a graduate seminar on Taiwanese Literary History in the Department of Chinese Literature.

Neither remnants nor commodities: Spirit objects in early twentieth century Chinese regional fiction

https://doi.org/10.1177/13591835211064426

Click Num:

Share